Building a Woodworking Shop

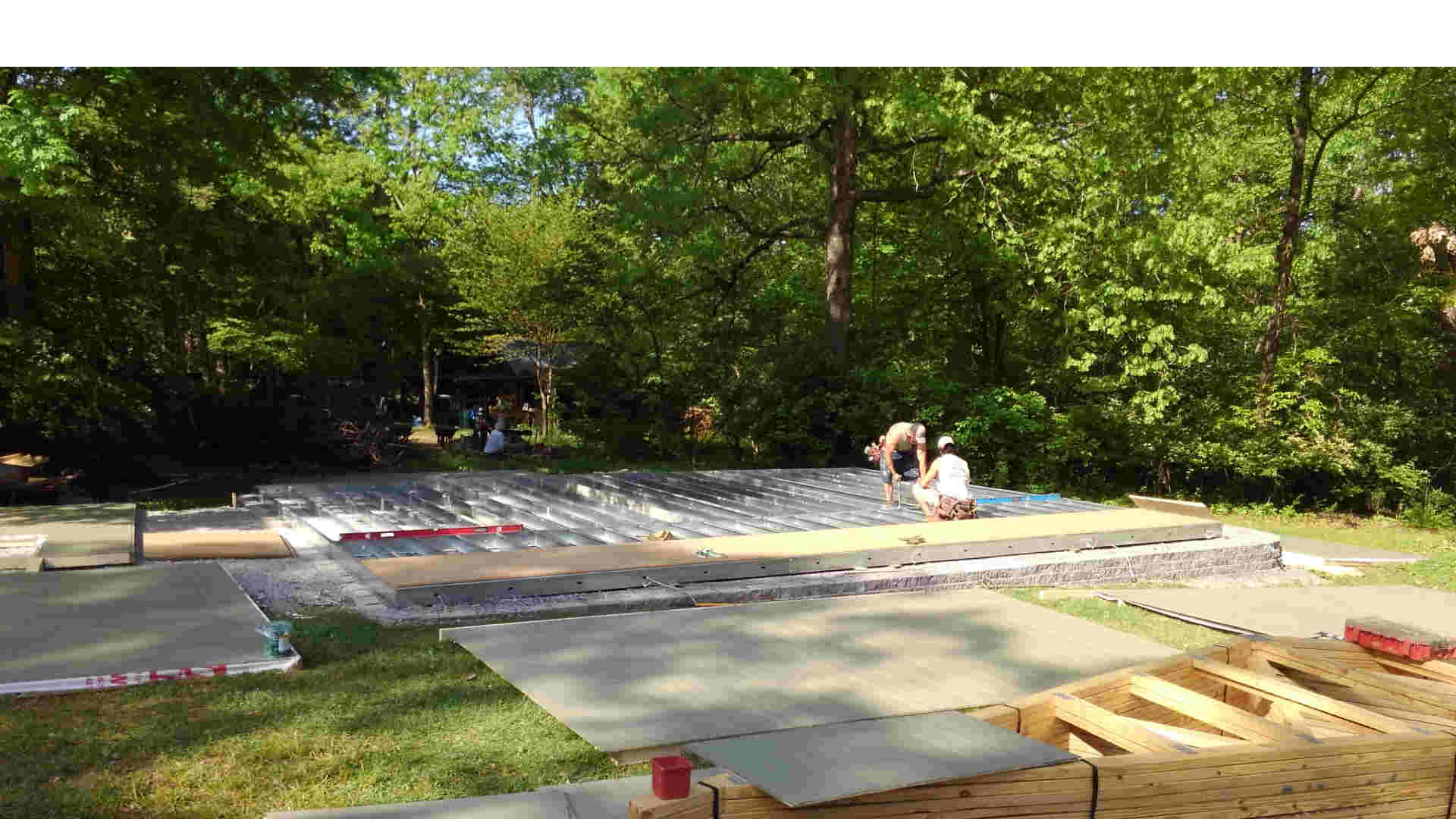

Now that the foundation for a 24 foot by 32-foot building is in place, it is time to put a building on the foundation. In the interest of time, we opted to have a Tuff Shed installed. I can certainly build a building on my own but I am just one person. I would have needed at least a month working every day to erect a building of this size. After examining the options, we found a reasonably priced alternative with Tuff Shed.

This building is designed to sit on top of a 6-inch thick metal joist system that will support the building and have the strength to contain all of the heavy Woodworking machines that we will be using.

Delivery Day for the Woodworking Shop

Having completed the foundation for our business, I thought I would get a day to relax. The installation of the shop was scheduled to begin on Tuesday and I was just puttering around moving a bit of gravel to level the driveway. Next thing I knew a big truck with trusses was backing in to drop them off. I’m glad they arrived but it sure would have been nice to have a bit of warning that they were expected.

Construction Day 1

Tuesday, I arrived at the job site early and waited for the installers to arrive. Around noon I finally got a call that said they were arriving in a few hours. They had the trailer loaded and were on the road from Nashville. They arrived about 2:30 and immediately got to work.

While it took them a bit to arrive, I was very impressed with the two installers. They were worker bees. They knew the process, where everything was on their trailer and in what order things needed to be completed. These two guys really didn’t need to talk much. They seemed to have the process down to a science. While one was laying out flooring the other set up to paint the finish coat on the walls and trim.

When it was time, he jumped in and helped to level and assemble the floor. The screw-guns got a workout and the floor joists came together quite quickly.

They got the floor laid out and partially assembled before the sun was set. They worked right up until the sun hit the horizon.

Construction Day 2

The next morning they arrived bright and early and got to work finishing the floor.

By noon they had the floor joists in place, screwed together and levelled. They really appreciated all of the work that I did to get a level foundation ready for them to work on. From what they said, they don’t usually get a foundation that is that well done and it sped up their job immensly.

After assembling and leveling they took a break and went to their warehouse for the flooring. After lunch, they jumped right into installing the floorboards then started erecting walls. By the end of day two, they had the walls up and secured ready to receive the trusses. I don’t think I heard them say two words to each other. They just seemed to know what the other guy wanted and when he wanted it.

While all this was going on, I watched. It was hard for me to just stand on the sidelines and do nothing but then again, it was nice not to have to lift and hammer and generally stress my body. Leaving it to the younger set was the right choice.

Construction Day 3

Thursday morning dawned bright and warm with a hint of clouds. The weatherman said that we were expecting showers in the afternoon and that an overcast day was forcast.

A third guy was added to their crew today. A younger man, he worked from the ground feeding things to the other two and generally being their ground man. Today was the roof raising day. First they built up the overhangs for the end walls and installed one of these on the back wall. Then they started carrying and putting the trusses into their places. They hand fed the trusses up to one guy on a ladder then lifted the other end up to another guy. The third guy, using a long pole then would swing the top of the truss up to vertical where it was secured to a temporary beam that set the level and fixed it in place until the sheathing could be added.

It was all a well orchestrated process. While the weather was overcast, there was no rain.

Their noon break saw all of the trusses in place and the sheathing was ready to start being installed. The afternoon was spent nailing sheathing to the roof and installing the metal roof decking. They finished the roof just as the sun reached the horizon.

An overcast day but fortunately the rain did not materialize. I hate to think how slippery that metal roofing would have been with a coating of water on top.

Construction Day 4

Now that the shed was up, all that was left was for the trim to be installed and touch up paint to be applied. Two of the guys worked on putting up the trim while the third one rolled on trim paint and touched up the main color.

This process kept them all busy for about 6 more hours and by 2 in the afternoon, they were all packed up and ready to call it a day.

There were 4 pieces of trim under the gable ends that weren’t included in their shipment so they were unable to complete the full job. They contacted their main office in Nashville and arranged to have the trim pieces shipped to the Knoxville warehouse. Then they scheduled a warrantee installer to come out and install the pieces.

After 2 trips where the installer was unable to complete the job due to insufficient tools Tuff shed finally sent out the Knoxville warehouse manager who was able to complete the job.

Results

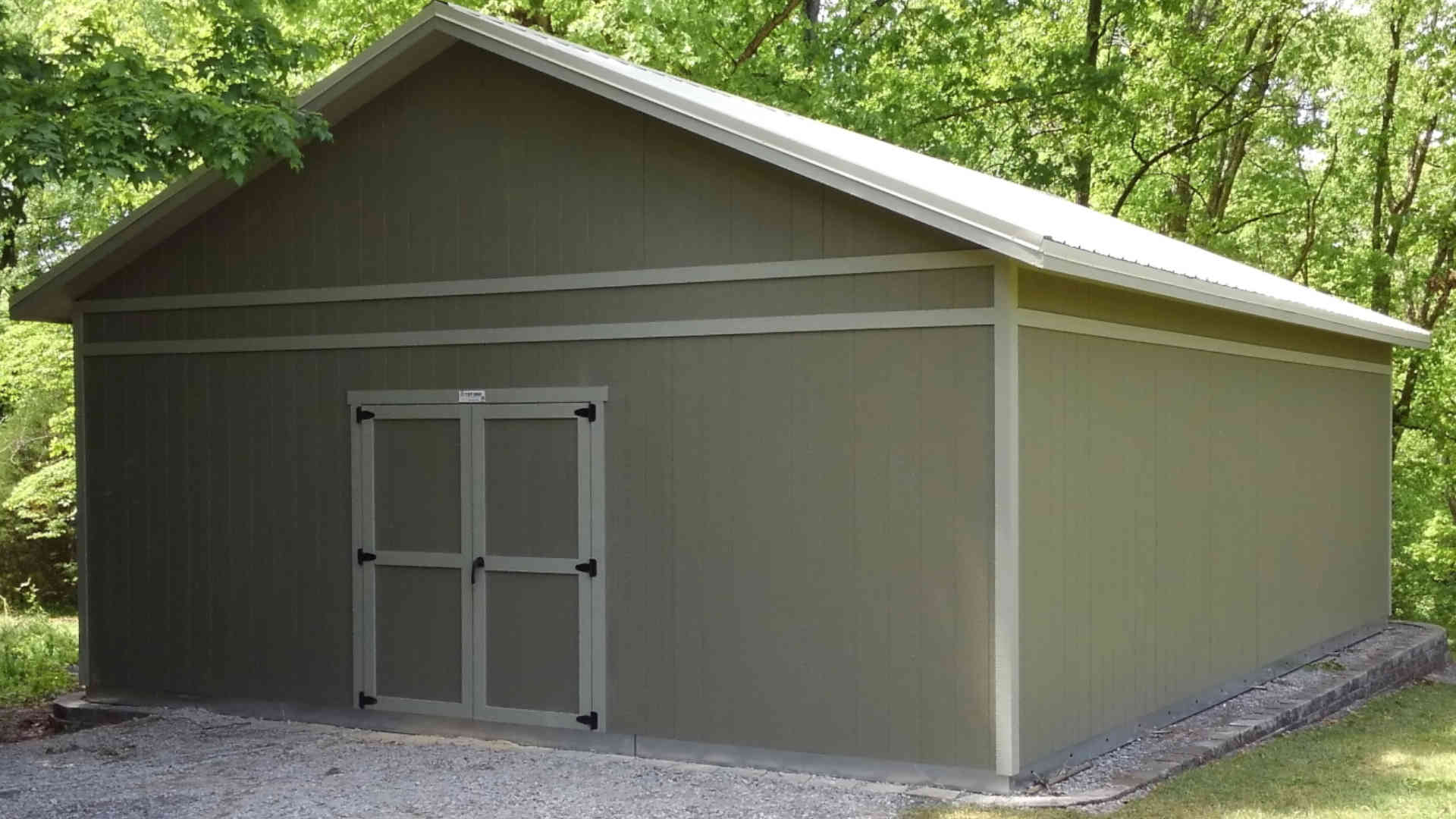

Overall the Tuff Shed meets our expectations. Getting the job finished and the quoting process was a major chore. But once we were able to nail down the design and get the main office in Nashville involved everything proceeded smoothly.

The one problem that we ran into was the location of the man door on the side of the building. It was located in the center of the building and we requested that it was located 8 feet from one end. There is an existing concrete pad located directly opposite the door. Eventually we will be using this for a finishing shed. I wanted to make an entry to the pad from the back of the building so that it was isolated from where sawdust is generated. Now, you will walk directly out the door onto the pad and there is a larger possibility to contaminate the finishing area with sawdust from the main shop.

The building, although the largest one that Tuff Shed has done, was well designed and went together with a minimum of modifications by the installers. If it weren’t for the salesperson here in Knoxville, the project would have been done in a very professional manner.

We were sent the drawings for the shed to provide to the building permitting office here in Knox County. These were exactly what was needed to fast track the permit. We needed to get an address for the shop so that the fire department knows were to go in case of emergency. That went without a hitch.

Our next challenge is to get the building wired and electrified.

My next post will discuss the process we are going through to get this done.